Key Takeaways

Your employer-sponsored 401(k) is a great tool to help kickstart your investment journey

Investing is the process of purchasing securities (i.e., stocks, bonds, mutual funds) with the goal of driving growth, income, or capital preservation

Let’s review some basics, including the importance of building positive investment habits and investing for the long-term

Getting started with investing can seem daunting at first, but it doesn’t have to be. This guide can help make it easy to familiarize yourself with investing. Because your 401(k) is a tool to help you save for retirement, this guide is written to help you think about long-term investments. We've also defined key terms below, for your convenience.

What is investing?

Investing is the process of purchasing securities (think stocks, bonds, mutual funds, etc.) with the goal of driving growth, income, or capital preservation. People may choose to invest their money because they want to improve their life or the lives of their loved ones.

For example, people invest money to help them become financially independent, cease working in retirement, and enjoy a comfortable standard of living in their later years. That said, investing is not a linear path, nor is there a guarantee of success.

How do stocks and index funds work?

Companies make it possible for someone to own a portion of them by issuing stock. When the company grows, the value of the stock grows, providing investors with a return on their investment. There are thousands of companies with stock available for purchase, and each represents the price someone is willing to pay to own a portion of that company. The prices of stocks fluctuate based on the buying and selling decisions of investors, which means that investors’ money can grow or lose value.

Instead of purchasing a single stock, it’s possible to purchase a group of stocks packaged together into what’s called an index fund (a type of mutual fund). Index funds track an index or “benchmark” of the overall performance of a market, such as the U.S. stock market. One such index is the S&P 500, which measures the performance of the 500 largest companies listed on the U.S. stock exchange. Since the S&P 500 covers a broad swath of companies across the economy and market, it can be used as a strong gauge of how the overall market is doing.

The advantages of index funds in long-term investing

An advantage of an index fund is that they’re tied to a mix of companies, industries, sectors, asset classes, or other classifications. If something were to happen in the auto industry, the financial impact you’d see in an index fund could be less than if you had invested in a single automaker’s stock. This can also help achieve diversification in your portfolio.¹

Picking stocks in an effort to outperform the market is difficult, even for expert investors. According to CNBC, index funds have historically outperformed many investment professionals that actively pick individual stocks to build portfolios.²

Index funds have a track record of performing better than many investment professionals that actively pick individual stocks to build portfolios.² Index funds also tend to have an advantage over actively managed mutual funds because they historically have lower fees, meaning investors get to keep a larger portion of the growth.

The stock market: Short-term swings vs long-term growth

If the stock market did well yesterday, it doesn’t guarantee another good day. Instead of looking at one particular year (or an even shorter timeframe), the stock market shows a different picture over the long haul.

These ups and downs, also called market volatility, can be a lot to stomach, especially when you see your account balance drop during downturns. But we believe it’s important to keep a longer-term focus on your portfolio since your goal is building wealth for retirement, which could be several years away.

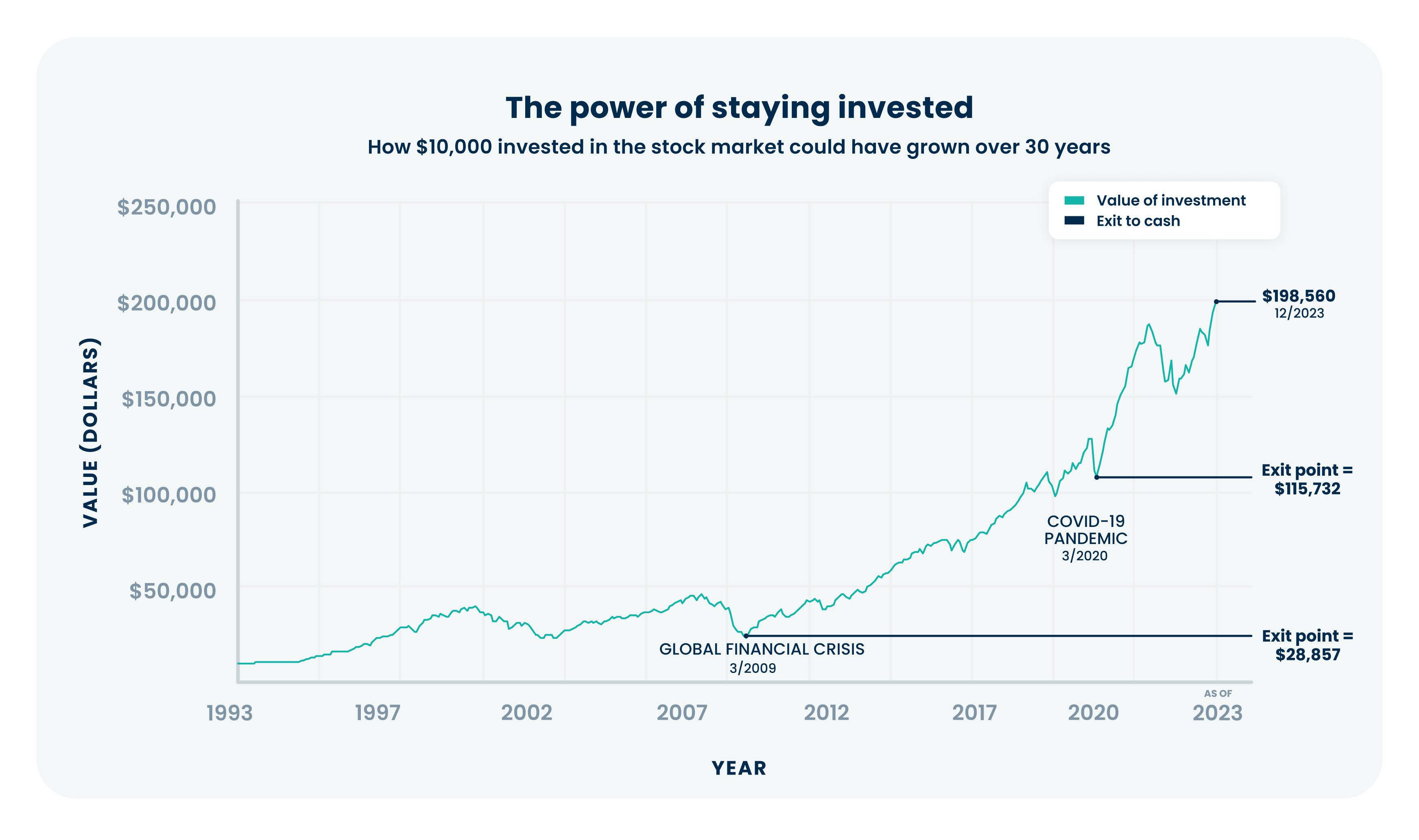

The power of staying invested

Let's say you have $10,000 to invest. Look at the chart below to see how could have grown over 30 years between 1992 and 2022. In this scenario, if you had kept your initial investment in the S&P 500, your $10,000 investment could have grown to over $173,000 by the end of 2022.

Past performance, including hypothetical performance, is no guarantee of future results. Investing is subject to risk, including the risk of loss. S&P data © 2023 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global. All rights reserved. Indices are not available for direct investment; therefore, their performance does not reflect the expenses associated with an actual portfolio. Chart is for illustrative purposes only. See more information below.³

But let's say you had decided to take all your money out of the market during the financial crisis in 2009. At that time, your investment would have been worth only about $29,000. Similarly, if you had converted into cash during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, your investment would have been worth $116,000. That's more than it would have been in 2009—but significantly less than it could have been if you’d stayed invested.

We can't control fluctuations in the economy, but we can control how we respond to those changes. While past performance doesn’t guarantee future results, the S&P 500 index—often considered a benchmark of U.S. stock market performance—saw annual average returns of about 10% from 1957 through December 31, 2022.⁴

What are the advantages of investing?

1. A greater chance at growing your money, especially over the long term.

Above, we compared how your balance could have changed if you had invested in the stock market compared to a savings account. Both of these options are better than not saving at all. One of the main reasons that people save or invest is because they know they need to be able to provide for themselves in the future.

2. Spending now could mean you'll pay for it later.

Money means choices. Because compounding growth can enhance the value of your savings, the pain of each dollar you save now can be greatly outweighed by the flexibility you could potentially gain in the future.

Example: You could spend $1,000 a year now on something you want (i.e., travel, dining out, clothes, or items for your home). Or, you could put that $1,000 into your 401(k) every year starting at age 30 and keep doing this until you reach retirement age (65). In the first case, you’d have spent $35,000 for $1,000 of fun every year for 35 years, but if you invested it, assuming a 7% return, you’d end up with a fund for your retirement that’s over 4x bigger — or, roughly $149,000.⁵

3. Government programs are unlikely to give you enough to retire on.

While many people talk about relying on Social Security in their later years, it may not be enough. Social Security payments will likely be too low and (and too unreliable) to retire without any other source of retirement income. The average amount that people get from Social Security is less than $18,000 per year. Do you think that will be enough to cover all of your expenses in retirement?

There’s also greater cause for concern. For years, people have talked about Social Security running out of money. The latest estimates suggest that the program will run out of funds as soon as 2034.

It’s important to keep in mind investing isn’t without its risks. Money that you invest now will be subject to market risks and your investment could lose value. That’s why it’s important to invest according to your personal financial situation, including your risk tolerance and time horizon.

Frequently asked questions

How do I get started with investing?

Your employer-sponsored 401(k) is a great tool to get started! Through your 401(k), you’ll have access to a variety of investments.

Choosing investments

If you have access to a 401(k) through your employer, you can automatically contribute a portion of your paycheck to your account. You will need to select investments aligned with your goals and risk tolerance (a process often referred to as choosing an asset allocation).

Depending on your company’s 401(k) provider, this can be a daunting process, especially if you’re not an experienced investor. Some providers, like Human Interest, provide employees with a selection of ready-to-go portfolios (model portfolios)⁶ that automatically invest your money in a diversified mix of low-cost funds so you don’t have to hand-pick from the tens of thousands of options that are available on the market.

How does Human Interest help me select a portfolio?

We use an online questionnaire to gather relevant information from you including your age, your intended retirement age, along with your comfort with tolerating ups and downs in the market (risk tolerance) and existing savings.

Our proprietary algorithm constructs your portfolio, or bundle of investments, tailored to your situation. We currently have 20 different model portfolios and we’ll recommend the one that is most suited to you, based on your responses.⁶ As you get older, we’ll automatically reallocate the investments in your portfolio so that they become more conservative as you get close to your intended retirement date. We also give you the choice to design and manage your own portfolio, if you prefer.

How do I build an investment habit?

Just like saving is a habit that can get easier with practice, investing is, too. Since you’re investing using your 401(k), you’ll need to figure out how much money you want to put in during a year and how to break that up across each paycheck. Read more in our guide: What is a 401(k) and how does it work?

One practice consistent with building the habit is called dollar-cost averaging. This is a strategy that involves steadily investing the same amount of money at regular intervals. It’s an intuitive way to invest (versus trying to figure out the “ideal” time, when the market is low) and can help ensure that you’re not always buying when prices are high.

How do I invest for the long-term?

You’re using your 401(k) to save for retirement. Focusing on a milestone, like retirement, that is likely years (or decades) away, you’ll need an investment strategy that aligns with your long-term goals. If anything, COVID-19 has taught us one strategy that you can apply to investing for retirement: Think of your 401(k) like your face. Don’t touch it.

Even though the market (and therefore your 401(k) balance) may go down some days, it’s more important to focus on how the market is doing over a longer period. While it may be tempting to try to sell investments when they lose value (or when you think they’re going to lose value), it’s nearly impossible to do this successfully even for experienced investors.

We believe that trying to time the market typically won’t be successful for most investors. We believe in holding investments in the market for the long term. Just remember: Focus on time in the market, not timing the market.

But what if I lose money?! Before you think about pulling money out of the stock market (or avoid investing in it altogether), read more about how to handle market volatility, i.e., what to do (and not do) when your 401(k) loses value.

Is investing for people like me?

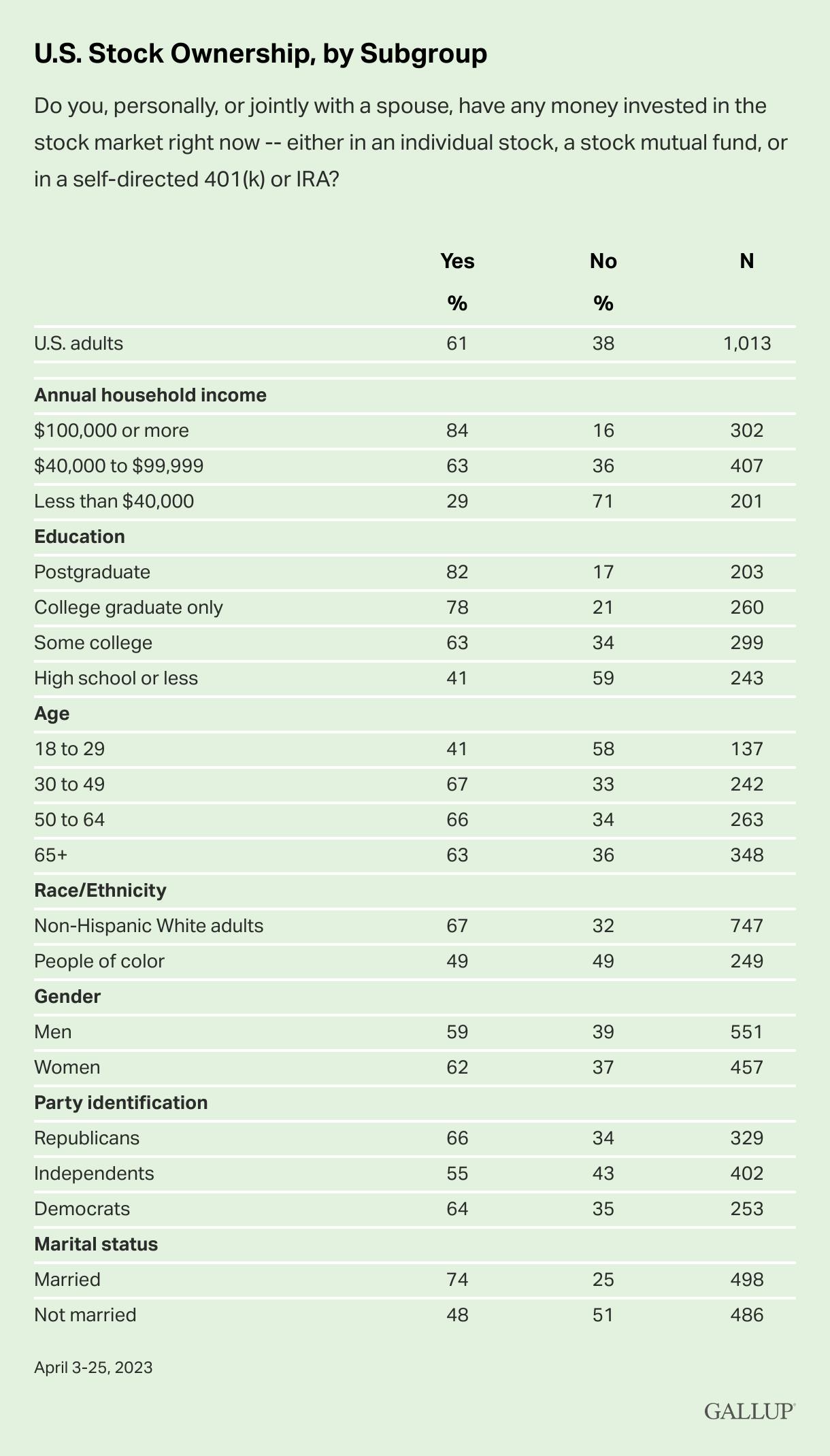

61% of households in the U.S. own stocks, the majority through a 401(k). Data from Gallup, in the chart below, show that investing is still more common today among certain demographic groups (white and affluent households). However, when given the chance to invest through a work-based retirement plan, people invest regardless of their income.

Human Interest data from 2020 found that employees who earn between $30,000 and $60,000 per year are putting away roughly 6% of their earnings into their Human Interest 401(k) plans (data is not inclusive of all 401(k) plans). Those who earn between $200,000 and $210,000 are investing closer to 8%.

Source: Gallup, 2023

Women and investing

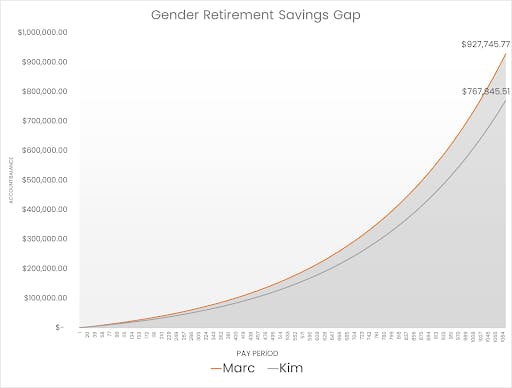

We talk a lot about the gender pay gap that exists in our society. According to a 2019 article from the American Association of University Women, women earn around 83 cents for every dollar men earn. In retirement, that gap is magnified. As a result, a woman’s retirement income could be hundreds of dollars less every month. That’s a huge difference in the quality of life that they could face in retirement. Not to mention, a woman’s retirement savings likely will need to last longer, based on women’s longer life expectancy.

Let’s look at the gender retirement savings gap, and how it is much larger than the gender pay gap. Assuming that a woman saves just as much as a man in the same role^, the gender pay gap makes a significant difference in savings at retirement when you compound that gap over the course of someone’s life.

Here’s an example with Marc and Kim, who each save 7% of their salary, but Kim only earns 83% ($43,160/year) of what Marc earns ($52,000/year).*:

*Results shown in this scenario are for illustrative purposes and are hypothetical in nature. It does not reflect actual investment results, transaction costs, or taxes, and is not a guarantee of future results. Assumptions include: Marc earns $52,000 per year and Kim earns $43,160 per year, they start saving at 25, they each save 7% of their biweekly paycheck, their retirement age is 67, and their investments yield 7% annual returns. Returns are rounded; assuming a 7% return annually, on average, compounding every biweekly pay period for 42 years.

^A review of more than 20,000 of our customers, from 2020, shows that men small business employees contribute slightly more (7.9%) of their salary to their 401(k) than women small business employees (7.5%).

Put your money to work

Money is a tool you can use to help reach your goals, and investing is a key long-term strategy that aims to put your money to work for your future. If you leave your savings in cash, it could cost you. The growth rate of the money you put in a savings account may not even keep pace with inflation, while the growth rate of the money you put in the stock market could be much higher, averaging around 7%, based on historical returns.⁴

What else do you need to know? Taking a long-term view is just what we do. Rather than chasing short-term gains, we focus on growing your nest egg using a long-term strategy. Read more about our investment philosophy.

Investing terms glossary: Help to get you going

Below is a glossary of common investing terms to help you get familiarized with investing concepts.

Asset allocation: The distribution of assets across various asset classes, such as stocks and bonds, often tailored to meet an investor’s objectives while considering risk tolerance and investment horizon.

Benchmark: A standard against which the performance of an investment portfolio can be measured.

Bond: A debt security that represents the borrowing of money by a corporation, government, or other entity. The borrowing institution repays the amount of the loan plus a percentage as interest. Income funds generally invest in bonds.

Bond fund: A fund that invests primarily in bonds and other debt instruments.

Diversification: Holding many securities or types of investments in a portfolio, often for the purpose of mitigating risk associated with owning a single security or type of investment.

Dollar-cost averaging: An investment strategy where you invest a consistent amount of money over time, e.g. $500 every two weeks, in the same group of assets. The goal of this strategy is to help you stick to an investment strategy rather than responding to the ups and downs in the market, which are difficult to predict (and trying to time the market tends to be a less effective strategy).

Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF): An exchange-traded fund is a type of security that involves a collection of securities—such as stocks. Similar to a mutual fund except that they can be bought and sold throughout the trading day whereas mutual funds can only be traded at market close.

Inflation: A rise in prices, which can be translated as the decline of purchasing power over time.

Mutual fund: An investment company registered with the SEC that buys a portfolio of securities selected by a professional investment adviser to meet a specified financial goal (investment objective). Mutual funds can have actively managed portfolios, where a professional investment adviser creates a unique mix of investments to meet a particular investment objective, or passively managed portfolios, in which the adviser seeks to match the performance of a selected benchmark or index.

Portfolio: A collection of investments such as stocks and bonds that are owned by an individual, organization, or investment fund.

Rebalance: The process of moving money from one type of investment to another to maintain a desired asset allocation.

Risk: The potential for investors to lose some or all the amounts invested or to fail to achieve their investment objectives.

Risk tolerance: An investor's ability and willingness to lose some or all of an investment in exchange for greater potential returns.

Stock: A security that represents an ownership interest in a corporation.

Stock fund: A fund that invests primarily in stocks.

Volatility: A statistical measure of the dispersion, or variability, of returns for a given security or portfolio.

Low-cost 401(k) with transparent pricing

Sign up for an affordable and easy-to-manage 401(k).

Article By

Ronnie CoxAs Investment Director for Human Interest Advisors (HIA), Ronnie’s responsibilities include market and economic commentary, analytical tooling and reporting oversight, and the investment manager search, selection, and monitoring processes. He chairs HIA’s Investment Committee, which sets strategic policy and direction of HIA's investment services.